"Wolf in the Fold" - Season 2, Episode 14

The Enterprise fights the ghost of misogynistic violence in itself.

Might it be time for the reckoning with Star Trek’s sexism? Early into Season 1, it’s clear that the show’s relatively progressive, egalitarian space-faring utopia still has a defined and regressive gender split. There’s only so much to expect from a mass-market television show in 1968, which is not offered as an excuse so much as an explanation. Women in Star Trek are ancillary to men. Uhura is the only regular female cast-member, female guest-stars are usually there to make eyes at one of the male leads, and female Starfleet uniforms had the skirts cut shorter than practical, cuts often made personally by showrunner Gene Roddenberry. A great “lover” of women in that he enjoyed sleeping with them, often illicitly, Roddenberry’s politics, or at the very least his writing, had a blind spot when it came to women. “Wolf in the Fold” is fascinating, and ultimately successful, because it portrays this blind spot in such a way as to auto-critique it. This is not a feminist text, but it makes a feminist point. That’s because it is the episode where the Enterprise kills the ghost of Jack the Ripper.

The ghost stuff is not as out-of-left-field as it may seem. Much like writer Robert Bloch’s last episode - the Halloween-themed “Catspaw” - “Wolf in the Fold” uses classical horror aesthetics with science fiction trappings. Bloch, the writer of the Psycho along with countless other horror stories and novels, clearly feels comfortable working in the genre, but here the production backs him up and helps deliver his best episode yet. The episode begins with a belly-dance for the benefit of the on-leave Kirk, McCoy, and Scotty, who are visiting the “pleasure planet” Argelius II. A hedonistic society oriented around feeling good all the time, the planet has seen no violence for decades, and it is the perfect place for a rehabilitative shore leave for a recently injured Scotty. Kirk and McCoy encourage the engineer to make a move on the dancer, who he invites on a walk through the fog strewn, Victorian-evocative Argelian streets. It’s here that the production first flexes, with a gorgeous, moody, seemingly gas-lit set design for the planet that forbodes the episode’s first twist: the dancer winds up stabbed, and Scotty is found holding the knife.

Kirk and McCoy find the first victim, a dancer named Kara. The episode’s opening segment is set amidst foggy, cobblestoned backstreets that may be foreshadowing the ultimate reveal; Victorian London is not far off the mind in this gorgeously lit set.

Off-screen, it seems Montgomery Scott has had a lot going on. McCoy mentions that an accident - caused by a female crew member - caused him head trauma and lead to “considerable psychological damage” including a “total resentment of women.” Despite this, McCoy and Kirk do not believe that their chief engineer has a murder in him - Scotty claims to remember nothing - and stick up for their crewmate after Argelian Administrator Hengist - recently reassigned from Rigel IV - moves to arrest him. The native Argelian leader, Prefect Jarvis, intervenes however, and states that the crime will be investigated in the old way by his wife, Sybo, who has the Argelian gift of empathic telepathy. Before they can even arrange the telepathic inquiry, another woman is found dead after bringing Scotty food. During the odd investigative seance - beautifully framed by director Joseph Pevney with a gorgeous overhead shot - Sybo is killed as well, but not before noting that she senses the “hatred of women” all around her. Women, it seems, do not survive encounters with Montgomery Scott.

The above mentioned seance, given by Sybo right before her death. Sybo, the dark haired woman at the bottom right, was played by Pilar Seurat, a Filippino-American actress whose ambiguous looks led her to be cast as a variety of diverse nationalities. Cultural and racial authenticity was not exactly high on the list of casting priorities in 1968, and Seurat often appeared as Hispanic, Asian, or Native American side characters in television throughout the decade.

After Sybo’s death - a dramatic affair in which she croaks out some unknown words as she passes - Prefect Jarvis allows the Enterprise to handle things its way. A hearing is held at which Scotty, the dancer’s husband, and the dancer’s father are put to a kind of lie detector. All pass, seemingly innocent. A deep dive into the computer reveals that one of the names Sybo said - “Redjac” - was a synonym for Jack the Ripper. Another - “Beratis” - was the name given to a serial killer on . . . Rigel IV.

Administrator Hengist does not keep his cool for long after this geographic coincidence is noticed. The knife that killed the dancer is found to be a Rigellian design. A string of murders across multiple planets - all mass killings of women - leads all the way back from Argelius II to Earth, circa 1888. Just when the Enterprise thinks it has its man though, it turns out it is not a man at all.

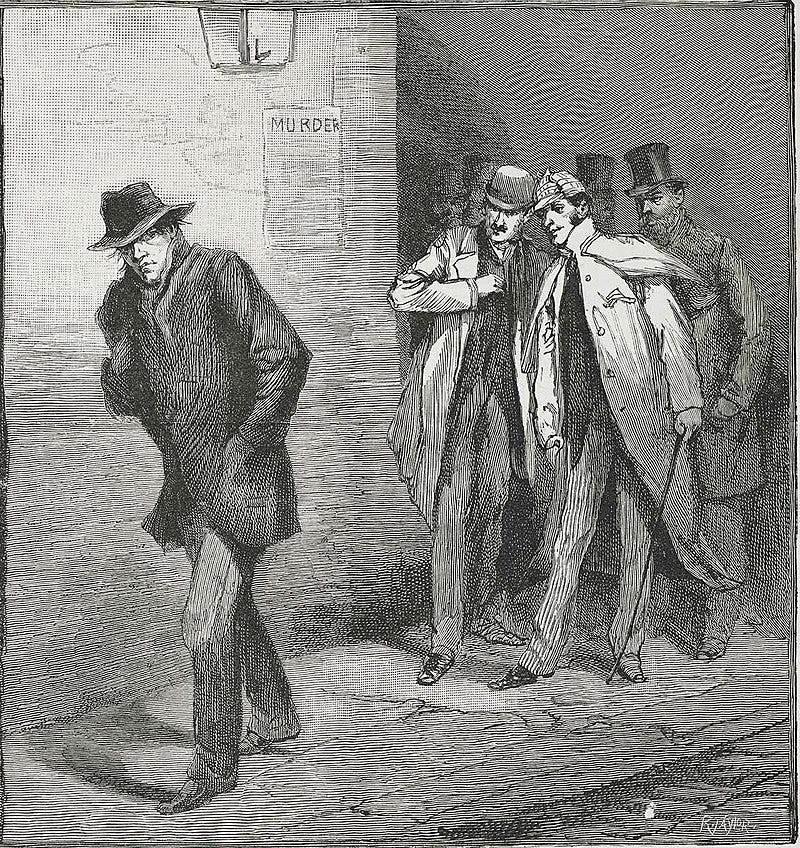

Hengist, right, threatens a drugged, unconcerned Yeoman. Hengist was played by John Fiedler, a ubiquitous character actor his time best known by his unique, high voice. He lent that voice to Piglet in Disney’s Winnie-the-Pooh adaptations, and also appeared in Sidney Lumet’s legal drama masterpiece 12 Angry Men (1957) as Juror #2.

With maniacal, echoing laughter, Hengist is revealed to be a mere vessel for an immortal, energy being that feeds on fear. This being - fairly called a ghost - is the real Jack the Ripper, having done murders throughout time by possessing the bodies of men around it. Jack leaves Hengist and possesses the Enterprise’s computer, broadcasting distorted, horrifying statements across the ship as he attempts to bring it down. Kirk and Spock take quick action - drugging the crew into a loopy, happy delirium to make them useless as possession objects and overloading the computer’s systems down by having it infinitely compute pi. This forces Jack back into Hengist, who is himself quickly drugged, before the crew beam him out of the ship at “maximum dispersion.” Sheer entropy is the only way to destroy this force of misogynistic violence.

Frankly, the central reveal of “Wolf in the Fold” - that the Enterprise would literally be fighting the literal ghost of Jack the Ripper - jolted me out of my seat. The Ripper, if he existed at all, was Western media’s first real confrontation with the idea of a “serial killer.” In the most agreed upon story, the Ripper - real identity unknown - killed five sex workers in London’s East End in the fall of 1888. This pattern of ritualistic gendered violence would find “new life” in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s as a wave of sensationalized, celebrity serial killers arose during that high-crime era. Serial killers now are big business; true crime shows and podcasts exploiting real murders of real women - almost always women - for lurid, cheap storytelling and profit are now a massive industry. Jack the Ripper, name unknown, is far more famous than his victims, as evidenced by the fact that you’ve almost certainly never hear of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly. By this measure, he is far more beloved as well.

What’s so telling about his use here is the way that the same lurid sensibility underlying true crime media leads to a kind of autocritique of Star Trek’s own sexism. Jack the Ripper is a shorthand synecdoche for serial killers because he was the first widely known; he can be an easy pull for a movie monster despite having (probably) been a real person, who did horrible things and suffered no consequence for them. Two hundred years later, he’s still famous. “Wolf in the Fold” is a model of doublespeak then. Its use of the Ripper reflects a casually disposable and caustic view of women - Spock at one point says women being “more deeply and easily terrified” accounts for the ghost targeting them - but its particular execution of a serial-killer story ends up a skewering metaphor of the impulse that led it to the story in the first place. After all, what better way to portray misogyny - Sydo psychically senses a “hatred of women” before her death - than as a ghost that lives through the ages and across planets, with men regardless of our technological advancements or escape to the stars? In the episode, the Ripper possesses multiple men to feed on the fear women have of them - Scotty included, his recent “resentment” of women completely illogical - and seems insatiable. The ghost simultaneously needs women to live and despises them because of that need. The ghost jumps to the machine, possessing even the impersonal logic of a computer to become a destructive force, a full 50 years before Mark Zuckerberg became a billionaire on the back of a website initially created to rate how hot college girls were. After the Enterprise’s crew destroys Jack, Kirk asks if anyone would like to go back to Argelius II, and look at some beautiful women.

I am under no illusion that Robert Bloch intended these readings or messages; instead I think he wrote a solid horror murder-mystery episode that is a good time to watch. It is by far Bloch’s best offering so far - after the forgettable “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” and the novel, if slight, “Catspaw” - by virtue of its intriguing set up and the excellent production from Pevney and crew. But it also contains an unintentional, expert metaphor for gendered violence as a whole. Much like how “Charlie X” explored the inherently childish nature of male entitlement, “Wolf in the Fold” explores its insidious, dangerously ephemeral nature as well. This is a great episode, an involving and twisty watch, and an unintentional artifact all at once.

Star Trek, as a whole, was a wildly progressive show for the time. This was a universe where men were united against common problems, solved those problems with diplomacy more than violence, and invented technology that took their good-natured aspirations to the stars. The Enterprise is staffed by men of all races, all nationalities, and even has an alien as second-in-command. But it is mostly men. Roddenberry’s blind spot, his wolf in the fold, was never more apparent.

Stray Thoughts

The episode features the first use of a “psycho-tricorder,” the above mentioned lie detector device, which can apparently perform a perfect mental scan of a person and reconstruct their memories as they truly happened. What a device, and you’ve got to wonder why it has not been used before!

The opening dance, photographed with wild attention, was performed by Tanya Lemani, who, if IMDb is to be believed, worked primarily in roles that require belly dancing. Behind the camera, she appears to have transitioned into location scouting and managing as she aged out of dancing in the 90s. What a fine career!

Photo Credits

"With the Vigilance Committee in the East End: A Suspicious Character" - Wikipedia, citing The Illustrated London News, October 13, 1888.